Tripcodes (Part 1): How Imageboards Built Identity on DES

Table of Contents

I haven’t seen too many posts on the inner workings of tripcodes so I thought it would be nice to do some analysis. This post is divided into two parts for easier readability, where the first part delves into how tripcodes work, and the second one explains how I built a WASM module to brute-force them and how it compares to C / CUDA alternatives.

What are tripcodes?

In the early 2000s, anonymous imageboards faced a tricky problem: how do you let users build identity without accounts, cookies, or any server-side state? Every post was ephemeral, and impersonation was common. Traditional authentication was unthinkable in anonymous culture, but some way to recognize repeat posters was essential. The solution turned out to be a quick hack. Two-character salt, a truncated password, and 25 rounds of DES.

2channel, a Japanese bulletin board founded in 1999 by Hiroyuki Nakamura, introduced a way for users to identify themselves through a password that would be processed and then mangled into a series of base64-like characters. Other people would see this and think, “oh yeah, this matches the one from the first (or another thread’s) post, so it must be them”.

They called them tripcodes (apparently the name came from ー人用キャップ, hitori-yō cap, or a cap for oneself), and look like this:

#abcd1234

#11112222

#./..ASDF..Here, # marks the start of the tripcode and the following characters are formed from a pool of a-zA-Z0-9./

Nowadays when we think of ways to make unique identifiers (outside of systems such as UUID) we may think of SHA-256 or SHA-3 which have gone through rigorous mathematical analysis and have proven hard to find collisions that violate the integrity of the digested data. However, this is early 2000s Japan we’re talking about. It’s also worth noting that 2channel did offer a modern SHA alternative years after that, but it didn’t spread too widely (as far as I know) and there are still multiple websites (notoriously 4chan, but also other sites unrelated to 2channel) using the former system.

How a tripcode is made

Speaking from a purely cryptographic point of view, any secure hash algorithm could be used against a password to generate a (practically) unique sequence of bytes, but this isn’t the only aspect to consider here. People visiting these websites needed to be able to identify at a glance whether that tripcode pertained to the person they wanted to talk with, so it couldn’t be too long (imagine seeing something like 54a59b9f22b0b80880d8427e548b7c23abd873486e1f035dce9cd697e85175033caa88e6d57bc35efae0b5afd3145f31 and having to compare every character by eye. Ew.) or too short, since it would be easy to find collisions of some kind. On the other hand, it should be fast enough to read (probably why the output is base64-like).

Maybe because DES was one of the first widely used encryption algorithms for non-military uses, or maybe because MD5 wasn’t widely used at first for password hashing, or even due to personal preference, all of this made 2channel opt for salted crypt(3)-style DES for the tripcode generation.

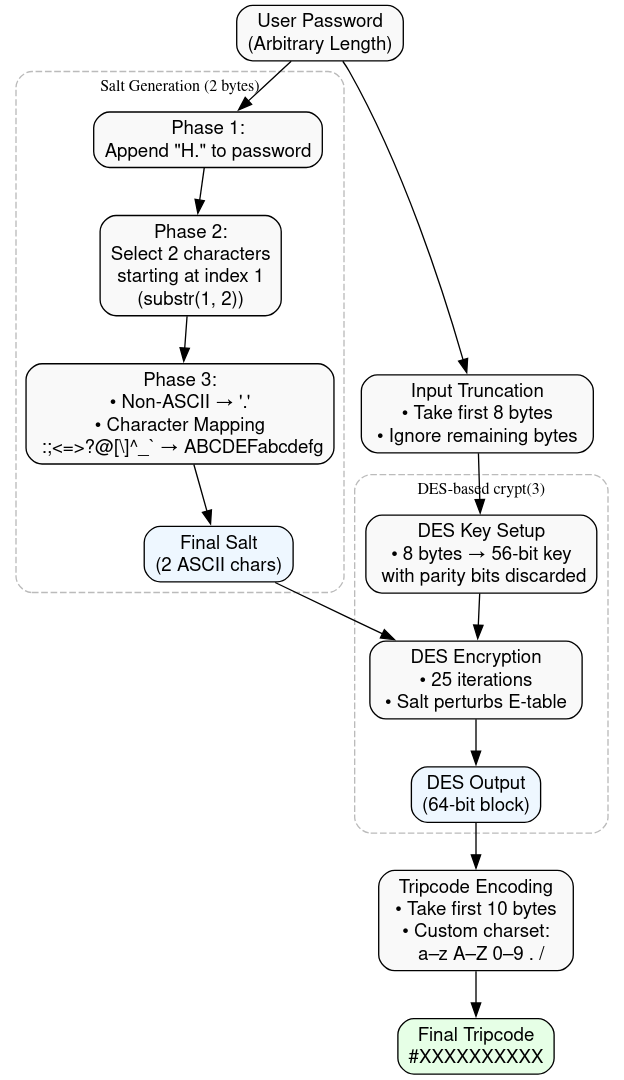

The steps 2channel followed to create an algorithm were:

- First, it took a series of bytes with a maximum of 8. If more than 8 bytes are provided, it ignored those after the 8th one. This means that with UTF-8, where some codepoints are multiple bytes wide, some characters would get truncated midway.

- A 2-byte salt was generated according to a custom generation from the password as well. I imagine the choice for this was to avoid rainbow table attacks because DES has a relatively low key space of 256 bits.

- Finally, it sent the data through 25 DES iterations and assigned a custom base64-like character for each group of 6 bits out of the first 60 (of 64) output bits. The 25-round implementation was probably inherited from Unix’s crypt(3) which intentionally weakened DES performance on old hardware.

Salt generation

A lot of symmetric-key algorithms allow for an extra input referred to as salt so that two people with the same (main) input can obtain two completely different results, which makes it harder for an attacker to precompute a list of hashes.

For (most) tripcode generation, this salt is reduced to 2 characters in the base64 range, that is, you would need to precompute 4096 rainbow tables for exhaustion (presuming zero knowledge of the salt function). In practice, this function rarely changes across implementations, rendering its point moot other than having to dedicate some computing power to processing it. Even if they didn’t, it would be relatively easy to brute-force a 2 character salt anyway.

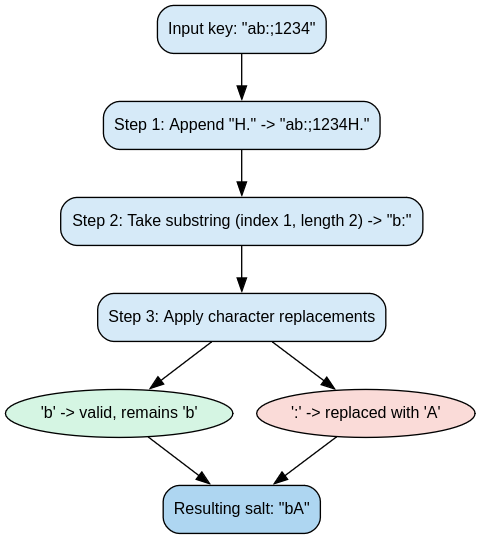

It goes through 3 phases:

- Phase 1: It appends “H.” to the string, ensuring an empty string won’t have an invalid salt. I don’t think the string itself has any meaning and it’s probably arbitrary.

- Phase 2: It takes the first two characters starting from the first index.

- Phase 3: It goes through a series of replacements (to be specific, it maps **:;<=>?@[\]^_`** -> ABCDEFabcdefg), and converts characters outside of the ASCII range to dots.

The resulting string is the salt that DES will use to perturb its expansion table.

DES and Crypt(3)

Before looking at how the final string is formed, let’s talk a bit about DES.

DES (Data Encryption Standard) is a 64-bit block cipher with a 56-bit effective key size (64 bits minus the last bit of parity in each byte), standardized in the late 1970s. By the time tripcodes were introduced it was already oldish, but as one of the first widely available civilian encryption standards it was everywhere, and one of the most popular implementations was crypt(3) on Unix.

crypt(3) does not use DES as a normal encryption primitive. Instead, it abuses it as a slow mixing function. The password (truncated to 8 bytes) becomes the DES key, the plaintext is fixed to all zeroes, and the result is fed back into DES 25 consecutive times. This was done so that brute-force attempts would take way more time than usual.

The salt, rather than being mixed into the key or input block, alters DES’s expansion table, meaning the same password under two different salts effectively produces two different outputs.

On tripcodes, it’s pretty much the same. The password is cut to 8 bytes, a 2-character salt is derived from it, and DES is run for 25 iterations. For tripcodes, DES is just used to squeeze a small input space into something that looks random enough.

Looking at it from 2025, DES has a small key space, the salt is tiny and deterministic, and the construction was never meant to resist parallelism. But for early-2000s imageboards the output was short, fast for servers to compute and implemented on PHP and other backend languages from the start.

We will look at DES more in depth in the second part. For now, let’s focus on the bigger picture of how tripcodes work.

Converting from DES output to a tripcode string

After going through all the DES rounds, the generation algorithm groups the 64 bit output into packs of 6 bits and replaces them according to the following table. The last 4 bits are discarded.

The table is a scrambled up base64 table with the same characters, which makes the effective output size of 6410 (260), regardless of DES’s 64 bit block size.

Cryptographic strength

It goes without saying that users should pick a strong password which isn’t too common. Assuming that most users will probably construct a password out of alphanumeric and common ASCII characters, we have 26 (a-z) + 26 (A-Z) + 10 (0-9) + (.-_,$%&/=^), making a total of 67 different bytes. Give or take. Which gives us around 678, or 576.480.100.000.000, possible inputs. While this doesn’t diminish the actual technical strength of tripcodes, I think it’s important to note how in practice, most of them would be probably easier to break than one would expect. Of course, most passwords will not be formed by 8 characters, but maybe 4-6 as people are lazy setting passwords (more so when the need of authentication isn’t present).

For comparison, the key space of DES (discounting parity bits) is 256. This is from a western point of view. Japanese users might appear to have access to a larger character set (hiragana, katakana, kanji), but byte-level truncation and multibyte encodings significantly limit the effective entropy gained in practice.

On the other hand, human error is indeed one of the main dangers of this system. It is made mainly for people, and so it’s easy to mistake two similar sequences. For example, consider the following tripcodes:

#SECURE.O./

#SECURE.0./

#TEST123456

#TESTI12346They are very similar, and to a tired eye or a quick reader, they look pretty much the same. This removes the need to find an exact collision a lot of the time, only having to look for similar ones for impersonation.

It’s also worth noting that the tripcode generation algorithm is publicly known, and several people have been trying to write software to brute-force the search as much as possible. I consider that this is mostly for three reasons:

- Pure curiosity and personal challenge.

- They want to be able to impersonate other users using a given tripcode.

- They want to stylize their own tripcode (technically speaking, they would look for a partial collision), searching (generally through a regular expression) a given sequence of characters they find appealing. For example, you may want to improve the readability of your tripcode by searching one that matches your username.

Computationally speaking, current approaches differ between those which are CPU and GPU bound, both making heavy use of CPU intrinsics and proprietary technologies such as CUDA to extract every bit of performance. With 2025 consumer-level hardware, one would generally measure CPU brute-forcing speeds in millions per second (M/s), and GPU speeds in thousands of millions per second (B/s).

Considering a GPU bound search with a speed of 2 billion (again, we are referring to billions here as thousands of millions, not millions of millions), or around 230.89/s, we would only need 36.028.787 seconds, or 417 days (2 days and a half for the human error scenario above). This shows that someone with enough resources to throw at a given tripcode could easily break through it.

In summary:

| Approach | Measured scale | Full search time estimate | Average search time estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | M/s | 45.6y (50M/s) ~ 228.34y (10M/s) | 22.8y ~ 114.17y |

| GPU | B/s | 208d (4B/s) ~ 834d (1B/s) | 104d ~ 417d |

| GPU (common cases) | B/s | 30h (4B/s) ~ 5 d (1B/s) | 15h ~ 60h |

Which would only be reduced by a similarity search.

Wrap-up

At a glance, this is the process we have seen in this part:

Thank you for reading. In part two, we will implement DES and tripcode search from scratch, making use of CPU intrinsics and transpiling the code to WASM order to run it directly in the browser. We will also look at both language-specific and general optimization techniques.